If you’ve ever picked up Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (or Sorcerer’s Stone in the US), breezed through its roughly 220–320 pages in a weekend, and then opened Order of the Phoenix only to discover a doorstopper of nearly 900 pages, you’ve probably asked the same question millions of fans have: Why do the Harry Potter books get longer as the series progresses?

The jump is impossible to ignore. The first book feels like a charming, self-contained children’s adventure. By book five, you’re deep in a sprawling war epic with hundreds of pages of Ministry politics, teenage angst, prophecy revelations, and extended dream sequences. Many readers love the growing scale; others find the later installments daunting. Either way, the increasing length is one of the most frequently discussed aspects of the series.

The short answer is that the books grow longer because the story itself grows up—with Harry, with its readers, and with J.K. Rowling’s ambition and confidence as a storyteller. The longer books are not the result of padding or publisher greed; they are the natural outcome of an expanding world, maturing themes, increasingly complex plots, and a narrative that gradually shifts from middle-grade adventure to young-adult epic fantasy with adult-level stakes.

In this in-depth guide, we’ll examine the exact word and page counts, trace the turning points, analyze the literary and publishing reasons behind the progression, debunk common misconceptions, and explain why the increasing length is actually one of the series’ greatest strengths. Whether you’re a first-time reader wondering why book four suddenly doubles in size or a longtime fan revisiting the series, this article will give you a clear, authoritative understanding of why the Harry Potter books get longer—and why that matters.

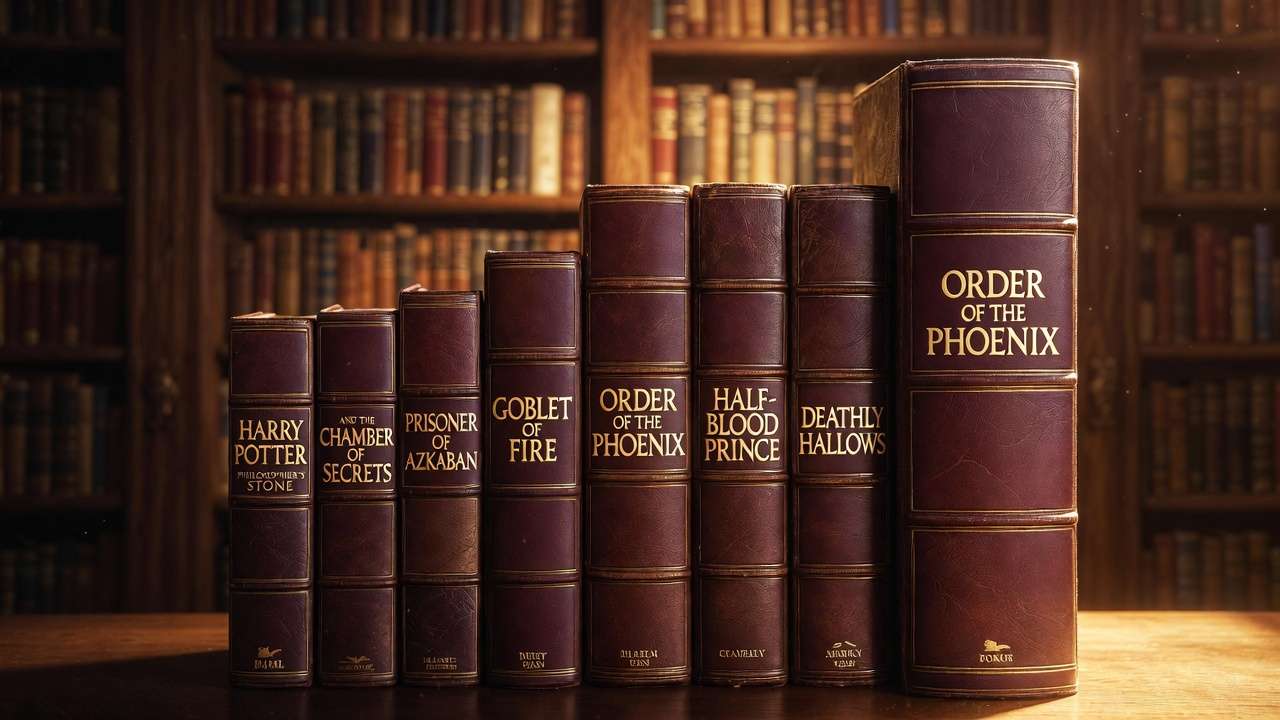

Harry Potter Book Lengths: Word Count and Page Count Breakdown

To understand the progression, let’s start with the numbers. Below are the approximate original UK hardcover word counts (the most commonly cited figures from Bloomsbury editions and J.K. Rowling’s own statements) alongside typical page counts for standard UK and US hardcovers at release.

- Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (1997) Word count: ~76,944 UK pages: ~223 US pages: ~309–320 (larger font/spacing)

- Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets (1998) Word count: ~85,141 UK pages: ~251 US pages: ~341

- Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (1999) Word count: ~107,253 UK pages: ~317 US pages: ~435

- Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2000) Word count: ~190,637 UK pages: ~636 US pages: ~734

- Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2003) Word count: ~257,045 (longest in the series) UK pages: ~766 US pages: ~870–912

- Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince (2005) Word count: ~168,923 UK pages: ~607 US pages: ~652

- Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (2007) Word count: ~198,227 UK pages: ~607 US pages: ~759

Total series word count: approximately 1,084,170 words.

Notice the pattern: modest increases in books 2 and 3, then a massive leap at book 4, the absolute peak at book 5, followed by a deliberate pullback in the final two volumes. These are not random fluctuations—they reflect specific creative and market decisions.

The Turning Point – Why the Dramatic Increase Starts at Book 4

The most striking change happens between Prisoner of Azkaban (~107,000 words) and Goblet of Fire (~190,000 words)—nearly doubling in length. This isn’t accidental; it marks a clear pivot in the series’ scope, tone, and target audience.

From Children’s Adventure to Epic YA Fantasy

The first three books were crafted primarily as middle-grade stories. J.K. Rowling and her UK publisher, Bloomsbury, were conscious of market expectations for children’s fiction in the late 1990s: keep it brisk, accessible, and under 100,000–120,000 words to avoid intimidating young readers or overwhelming parents buying for 8–12-year-olds.

Goblet of Fire changed everything. The introduction of the Triwizard Tournament required:

- Detailed descriptions of four massive tasks

- An international Quidditch World Cup opening chapter

- The arrival of foreign schools (Beauxbatons and Durmstrang)

- Multiple new characters (Viktor Krum, Fleur Delacour, Madame Maxime, Igor Karkaroff)

- The full return of Voldemort in a graveyard sequence

These elements demanded space for world expansion, subplots, and tension-building that the earlier, more contained school-year mysteries simply didn’t need. Rowling herself noted in interviews (including a 2000 BBC special) that she had always envisioned the series growing darker and more complex, but the early books were deliberately restrained to build readership gradually.

The “Harry Potter Effect” on Publishing

By the time Goblet of Fire was published in 2000, the series had become a global phenomenon. The first three books had sold tens of millions of copies worldwide, proving that children and young teens were not only willing but eager to read longer, denser fantasy novels.

Publishers—Bloomsbury in the UK and Scholastic in the US—realized they no longer needed to enforce strict length limits. The audience had matured alongside Harry, and the market had shifted: epic fantasy for young adults (think early Eragon, later Twilight and Hunger Games) was gaining traction precisely because of Rowling’s success.

After Goblet, there was no commercial pressure to keep books short. In fact, the opposite became true: fans expected—and publishers welcomed—more expansive storytelling. This freedom allowed Rowling to write at the length the story required rather than the length the market initially demanded.

Key Reasons the Books Grow Longer – In-Depth Analysis

The increasing length isn’t a flaw; it’s the direct result of several interlocking factors that reflect both artistic evolution and narrative necessity.

Maturing Characters and Themes Mirror Reader Growth

Harry begins the series as an 11-year-old orphan discovering magic. By Order of the Phoenix, he is 15, dealing with grief, teenage rebellion, first crushes, authority figures who lie to him, and the psychological toll of being Voldemort’s prophesied enemy.

This maturation requires more page space:

- Extended internal monologues and emotional processing (especially in Order during Harry’s anger and isolation)

- Romantic subplots (Harry/Cho, Ron/Hermione tensions)

- Moral complexity (Dumbledore’s flaws, Snape’s ambiguous motives, Sirius’s recklessness)

- Themes of death, sacrifice, prejudice (SPEW), corruption (Fudge’s Ministry), and propaganda

A shorter book simply couldn’t accommodate the depth needed to make these developments feel earned rather than rushed.

Expanding World-Building and Plot Complexity

The wizarding world grows exponentially:

- Books 1–3 mostly stay within Hogwarts and the immediate vicinity.

- Book 4 introduces international wizardry, the Ministry in depth, and Voldemort’s full organization.

- Book 5 shows the Ministry’s inner workings, the Department of Mysteries, the full Order of the Phoenix network, and wizarding politics.

- Books 6–7 add Godric’s Hollow history, Dumbledore’s past, Horcrux locations across Britain and Europe, and the mechanics of soul magic.

Each new layer—new spells, magical theory, historical backstory, side characters—requires description, explanation, and integration into the main plot. Rowling’s rich, immersive style (long descriptive passages, witty dialogue, detailed settings) naturally expands to fill that space.

J.K. Rowling’s Evolving Confidence and Style

Rowling has spoken openly about her editing process. Early manuscripts were heavily cut by her editor, Barry Cunningham, and later by Arthur Levine at Scholastic, to fit children’s-market expectations.

Once the series exploded, Rowling gained near-total creative control. She could keep scenes she loved—such as the extended Weasley family Christmas in Goblet, the full DA meetings, or Dumbledore’s detailed lessons in Half-Blood Prince—without fear of length restrictions.

Her prose also became more confident: longer sentences, richer vocabulary, more layered foreshadowing. What began as a tightly edited debut evolved into an author writing at full throttle.

Narrative Pacing and Multiple Storylines

Later books juggle several simultaneous arcs:

- Harry’s personal growth and relationships

- The Horcrux quest

- Dumbledore’s private investigations

- Voldemort’s public campaign

- The resistance movement (Order, DA, etc.)

Interweaving these threads while maintaining suspense, planting clues, and delivering payoffs requires breathing room. Cutting them short would flatten the emotional stakes and weaken the climaxes.

How Increasing Length Enhances the Series (Literary Benefits)

Far from being a drawback, the growing page counts are one of the strongest elements of J.K. Rowling’s achievement. Here’s why the extra length actually improves the reading experience and elevates the series from good children’s books to a landmark work of modern fantasy literature.

First, longer books allow for true emotional immersion. The grief Harry feels after Sirius’s death in Order of the Phoenix isn’t conveyed in a single chapter—it builds over dozens of pages of sullen silences, angry outbursts, isolation from friends, and eventual cathartic conversations. A shorter book would have reduced this to a quick montage, robbing readers of the chance to feel the weight of loss alongside Harry.

Second, the extended length supports masterful foreshadowing and payoff. Details planted in book four (the Pensieve glimpses of Death Eaters, the prophecy orb, the Department of Mysteries layout) don’t fully detonate until book five—and some echoes continue all the way to the final battle. The space gives Rowling room to layer clues subtly, reward attentive readers, and create those satisfying “aha” moments on re-reads.

Third, it mirrors real adolescence. Harry doesn’t leap from wide-eyed eleven-year-old to battle-hardened seventeen-year-old overnight. The gradual expansion of the narrative pace parallels the way teenagers experience time: school years feel endless, friendships intensify slowly, crushes consume entire summers, and small betrayals cut deeply. The books lengthen because Harry’s world—and the reader’s emotional investment in it—has expanded.

Finally, the epic scale matches the stakes. By Deathly Hallows, the conflict is no longer about winning house points or passing exams; it’s about the survival of the entire wizarding world and the moral cost of victory. A slim novel simply couldn’t carry that gravitas.

Common Misconceptions About Book Length

Several myths persist about why the books get longer. Let’s address the most frequent ones.

- “They’re just padded with unnecessary filler.” Almost every extended scene serves a purpose. The long DA training chapters in Order build Harry’s leadership skills and group dynamics. The wedding sequence in Deathly Hallows establishes the atmosphere of a world under siege. Even seemingly “slow” sections advance character or plant future plot seeds.

- “The US editions are longer because they add content.” No—the US versions often have more pages due to larger font, wider margins, and different paper stock, but the text content is virtually identical to the UK editions (minor word-choice differences aside, e.g., “Mum” vs. “Mom”).

- “Rowling got paid by the word after she became famous.” While she did gain creative freedom, there’s no evidence of mercenary padding. Rowling has consistently said she wrote what the story demanded, and editors still trimmed where necessary (e.g., significant cuts were made even to Deathly Hallows).

- “Longer = better.” Not always. Some fans prefer the tighter, more magical feel of the first three books. The length works because it suits the story’s evolution—not because longer is inherently superior.

Reader Tips for Enjoying the Longer Books

If the heft of Order of the Phoenix or Deathly Hallows ever feels intimidating, try these practical strategies:

- Break it into manageable chunks: Treat each book like a TV season—read 5–10 chapters per sitting, using natural breaks (end of term, major plot turns).

- Use audiobooks for momentum: Jim Dale (US) and Stephen Fry (UK) narrations turn long stretches into immersive listening experiences—perfect for commutes or chores.

- Re-read strategically: The later books reward multiple reads. On first pass, focus on the main plot; on subsequent reads, notice the foreshadowing and character nuances that justify the length.

- Embrace the “growing up with Harry” mindset: The increasing length is intentional—it asks you to mature alongside the characters. Accepting that shift often transforms frustration into appreciation.

- Track your progress visually: Some fans mark chapter milestones or use reading trackers to see how quickly the pages disappear once immersed.

FAQs About Harry Potter Book Lengths

Why is Order of the Phoenix the longest book? It contains the most subplots running concurrently: Harry’s Occlumency lessons, Umbridge’s tyranny, the DA’s formation and secrecy, the full prophecy reveal, the battle in the Department of Mysteries, and extensive Ministry politics. Rowling needed space to balance teenage drama with escalating war tension.

Did J.K. Rowling plan the increasing lengths from the start? Partially. She always knew the series would darken and expand, but early publisher caution kept the first books shorter. Once the audience proved ready for more, she wrote at the natural length each story required.

How do page counts vary by edition or language? Dramatically. Illustrated editions add 50–150 pages. Translations can be longer or shorter depending on language efficiency (e.g., German and Russian editions often exceed English page counts due to compound words and sentence structure).

Did the movies cut a lot because of length? Yes—especially Goblet of Fire, Order of the Phoenix, and Half-Blood Prince. Entire subplots (S.P.E.W., the full Quidditch World Cup, most Dumbledore memories) were removed or condensed to fit runtime constraints.

Has Harry Potter influenced longer children’s/YA books overall? Absolutely. Before 2000, few children’s novels exceeded 150,000 words. Post-Potter, epic-length YA fantasy (e.g., Inheritance Cycle, Mistborn, Throne of Glass) became standard, proving young readers crave depth and scale.

The Harry Potter books get longer because the story demands it. What begins as a light school adventure must evolve into a full-scale war epic. Harry grows from child to young man; the wizarding world expands from a hidden school to an entire society under threat; themes deepen from friendship and wonder to sacrifice, prejudice, love, and the cost of power. J.K. Rowling’s increasing confidence, combined with a proven global audience ready for complexity, allowed her to give the narrative the space it needed.

The result is not bloat, but richness—a series that grows with its readers, rewarding those who stay with it through every extra page. The length isn’t a barrier; it’s proof that the story became too big, too important, too human to be contained in slim volumes.

So the next time you pick up Order of the Phoenix and feel its weight in your hands, remember: that thickness is earned. It carries five years of growth, hundreds of secrets, and the fate of a world.

Which book’s length surprised you the most when you first read it? Do you prefer the tighter early books or the sprawling later ones? Drop your thoughts in the comments—I’d love to hear how the series’ evolution felt for you.